How Habits Can Make Idiots of Us All

The “power of habit” works both ways, unfortunately …

Years ago I heard of an experiment supposedly performed at the Yerkes Primate Research Center in Atlanta. What they did, so the story goes, was to put a scaffold in the chimpanzees’ rec room with an enormous bunch of grapes perched on top.

Apes, in case you are unaware, adore grapes!

Unbeknownst to the chimps, however, a motion sensor had been pointed toward the upper regions of the scaffold and wired to the room’s sprinkler system. So that whenever a chimpanzee climbed the scaffolding to snatch the fruit, the sprinklers kicked on, drenching everybody in a cold shower. It didn’t take long for the chimps to start ignoring the grapes.

But then, the researchers began moving chimps out of the group and bringing new ones in, one at a time. And sure as sunrise, the newb would make a beeline for the scaffold. But as soon as he set foot on the first rung, the nearest old timer would yank him down and everyone would commence to kick his ass. And thus, peace, order, and comfort were preserved for the community.

Then came the day when the last chimp who had actually witnessed the sprinklers being triggered was rotated out. As the scientists observed from behind their reinforced glass window, pencils hovering above clipboards, the replacement was allowed into the room. They watched intently as he surveyed his surroundings, scoped the scene for friendly faces, caught sight of the scaffold, and lit up with excitement when he beheld, wonder of wonders, the platter of grapes. Which, to his apparent amazement, no one else seemed to notice!

Taking advantage of this incredible stroke of luck, the newcomer launched himself at the bars, grabbed hold of them, and immediately found himself at the epicenter of a furious screeching beatdown. The rule of law had been preserved.

Thou shalt not climb the scaffold!

Amen and amen.

Now, if one were somehow able to ask these chimpanzees why it was that climbing the scaffold earned an ass-whupping in that particular rec room, there’s little doubt what the answer would be: some chimp version of “That’s just how we do things around here.”

Perhaps a particularly philosophical chimp might even invent a rationale. “Well, there aren’t enough grapes for everybody, so to be fair it was decided no one should eat them.”

“And who decided that?”

“I dunno, that was before my time. Makes a lot of sense though, doesn’t it?”

Apocryphal though this experiment may be, it nonetheless illustrates a process we humans have all experienced. (By all means, do share your own examples in the responses!) The force of habit is strong.

Who moved my cooler?

Back in the 1990s I managed a bar for a steakhouse in Gainesville, FL. Right inside the door connecting the kitchen to the back bar stood a lunky glass-cooler. It was in the way and facing the wrong direction, and caused bartenders to cross paths when someone needed chilled glass. Just about the worst position it could occupy. Taped to the front was a laminated sign:

DO NOT MOVE THIS COOLER

Now this corporate-owned restaurant was a chokepoint for managers. It was profitable, ran tight, and sat in a middle market. Managers who did well there got promoted to open slots in larger markets like Orlando or Tampa. Those who screwed up got dumped. (Here’s looking at you, Sonny. How’s the strip bar scene these days?) So we ran through a lot of GMs.

One of the first things I wanted to do was move that damn glass-chiller, but the GM put the kibosh on that idea. He had no clue why the cooler couldn’t be moved, but there had to be a reason. Best not to tempt fate.

I asked everybody there why that cooler couldn’t be moved. Indifferent shrugs were all I got in reply. Until I asked Pat, the oldest employee in both age and tenure, a server who worked only the smoking section because she said smokers tipped better. (Yes, young folk, you could smoke in restaurants back in the Stone Age.) “Oh yeah,” she told me, “that was for Tim’s tea.”

“Say what?”

“Tim Theo, old manager. Liked his tea in a chilled pint. Wanted the cooler right by the door so he could grab a cold glass without walking into the bar.”

“When did Tim leave?”

“Mmm, bout eight years ago, I suppose.”

Thus, the cooler was relocated. And there was much rejoicing.

Chick-fool-A

What made me think of all this was a traffic jam outside the Chick-fil-A down the street from my house yesterday.

Now, for those of you who do not live in the Deep South of the U.S., you must understand that Chick-fil-A is a fast food restaurant specializing in chicken sandwiches which, on the Southern cultural totem pole, ranks just below football and Jesus, in that order. When a Chick-fil-A came to my hometown in the early 1980s, the police had to be called out to direct traffic so as to avert the formation of citywide gridlock, and a potential black hole singularity, due to the sheer onrush of traffic streaming in from all quarters of the town and several adjoining counties.

When the pandemic hit back in 2020, the Chick-fil-A here responded with the precision of a Swiss watch. Cones and signs went up, funneling traffic into a double track around the building which merged just short of the window. Impeccably groomed Christian youth fanned out in their red shirts, black pants, and visors, geared up with wireless headsets and tablets, to take orders along the lines of cars come rain, snow, or shine. Parking spots were designated for any vehicle that had to wait for an order so that the others could proceed smoothly to the pay window where a valet stood with a tray, ready to convey payment in one direction and hot food in the other. From heaven, Gottlieb Daimler and Karl Benz gazed down in envious astonishment at the efficiency of this parking lot.

Yet even this masterwork of people-management was no match for the overwhelming popularity of the Chick-fil-A sandwich. On a regular basis, traffic backed up onto the shopping center access lanes and, from there, out into the public thoroughfare as folks sat in their vehicles for up to ten minutes at a stretch to get their bags of food.

Eventually, though, the virus waned and the dining room once again opened its doors. But by then, after many months of conditioning, folks had gotten used to ordering from the parking lot. The lobby remained a ghost town and the traffic jams formed like clockwork every morning, midday, and evening (except Sundays, mind you). From time to time, a savvy soul would park in the adjoining lot, stroll into the restaurant, order their food, and after a minute or two saunter back out in full view of the idling caravan. And yet, the lines formed and re-formed, day after day, week after week.

Now I know what you’re thinking. Maybe folks opted for the drive-through out of precaution against covid. Let me remind you that we’re talking about a Chick-fil-A in Georgia, where the clientele is redder than Rudolph’s nose on a hot date. These are not “Honey, where’s my mask?” kind of people.

Nope. They just got used to doing it that way. And as long as most everyone else keeps creeping around that lot, they will too. Perhaps if the local football coach were seen walking into the store, the log jam would break and things would return to normal. But so far, that hasn’t happened.

Question everything

At some point in our lives, it seems to me, we should question everything we do. And I mean that literally.

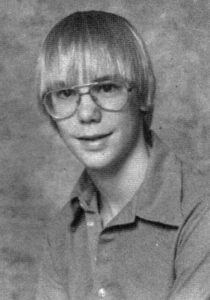

When I was a kid, I was shy, goofy, and scrawny, and had a bizarre inability to recognize bad haircuts. I had one near-sighted and one far-sighted eye (still do) which not only made me clumsy, but also meant I only used one at a time depending on where I was looking, so after a while the other would just go wandering off on its own. Naturally, I was a walking “Please bully me!” sign.

For whatever reason, it took until my mid-forties for me to physically and mentally relax and stop assuming that random people might just decide to assault me at any moment, despite the fact that this hadn’t happened since I stopped riding the school bus. Life got a whole lot better after that.

A few years ago, I decided to start taking my Zen practice more seriously. And since then, it’s dawned on me how much stuff I’ve been dragging around with me that I have no real use for. A lot of it, I’d been thinking I’d “get around” to using, but truth was, I liked to imagine myself as the kind of person who would have those things, who would engage in the kinds of activities they implied, someone who was a much better musician than I am, tougher than I’ve ever been, a snappier dresser, a connoisseur, hail-fellow-well-met and all that.

And so began the slough. And not just of things, but of habits. “Do I really need to —?” pops into my head a lot these days. And not infrequently, the answer is “Nope.” When that happens, I just let go, let whatever-it-was drop away. And invariably, I breathe a tad easier for the loss.

I suppose one day I’ll end up living in a couple of rooms somewhere with five changes of clothes, a few pots and pans, my old Taylor guitar, a bed, and a sofa. Or maybe not, who knows? But I’m open to the possibility.

That’s what life seems to be teaching me as I age. Be open to the possibility. Look for the ruts and be willing to step out of them if they’re not headed where you really want to go anymore. Especially if they never were.

And maybe, one of these days, figure out a way to get those grapes off the scaffold where everyone can get at them. So what if the bigger chimps hog them all? Worst that could happen, you’ll make a lot of new friends.

Header image by Ulrike Leone (edited by author)

Read every story from Paul Thomas Zenki (and thousands of other writers) on Medium.

Paul Thomas Zenki is an essayist, ghostwriter, copywriter, marketer, songwriter, and consultant living in Athens, GA.