Not a member of Medium? Read every story from Paul Thomas Zenki (and thousands of other writers on Medium) by subscribing today. Your membership directly supports Paul Thomas Zenki and other writers you read. Click here to join.

Every Springsteen Album, Ranked: 0-5 Cadillacs

A man, his music, and his cars …

Billy Joel started this.

It was back in the early ’80s, around when Joel’s “Uptown Girl” video was rotating on MTV. I read this magazine interview, he was asked something about the path to there from Glass Houses and from Piano Man before that. Joel said he had to mix it up to keep things interesting for himself and the audience.

Otherwise… “I mean, I love Bruce, but get out of the car, man.”

Which got me wondering — just how often does Bruce Springsteen sing about cars? Well it only took me three and a half decades to get off my ass and go count.

I’ve decided to rank the first-release material on each studio album, including retrospectives, from 0 to 5 Cadillacs in half-Caddy units, representing the percentage of “car” tunes, i.e. tracks mentioning of course cars but also driving, riding, hitch-hiking, racing, engine repair, car washes, motorbikes, all that kind of thing. Then, Springsteen’s entire body of work, including all the songs not on those records, is ranked on the same scale.

Let’s roll!

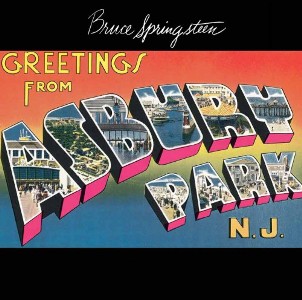

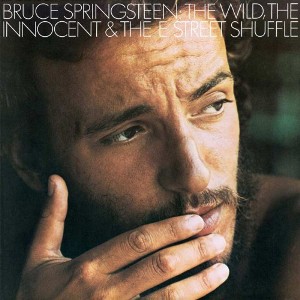

Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. / The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle

It starts in 1973. Kinda quietly, actually. Springsteen’s first two albums, released the same year, didn’t really take off until Born to Run made him a rock star in ’75.

If you’re young it may seem weird how many reviewers compared Greetings to Bob Dylan. Because musically, this album’s all Bruce — infectious guitar riffs, swinging saxophone, tinkling piano interludes, check check check.

Lyrically, though, we don’t see him so clearly yet. Leaning hard on Dylan’s post-folk work, Greetings hosts a carnival of characters in phantasmagoric scenes like this one from “Does This Bus Stop at 82nd Street”:

Wizard imps and sweat sock pimps, interstellar mongrel nymphs

Rex said that lady left him limp. Love’s like that (sure it is).

Queen of diamonds, ace of spades, newly discovered lovers of the everglades

They take out a full page ad in the trades to announce their arrival

And Mary Lou she found out how to cope, she rides to heaven on a gyroscope

The Daily News asks her for the dope

She says “Man, the dope’s that there’s still hope”.

But the two songs that would get radio play for Bruce weren’t even on the first cut of the album, which Columbia rejected because they didn’t hear a hit single. To give a sense of the lyric genius lurking behind that frontal assault of images there, Springsteen told them “Be right back” and returned with “Blinded by the Light” and “Spirit in the Night,” the tunes that introduced his first radio fans to his work in the early ’70s, myself included.

Despite not yet finding his own lyrical lane, Bruce peels out hot here, with cars or riding mentioned in every single tune on the record for a perfect 5 Caddies. Most of these are incidentals like “Early-Pearly… asked me if I needed a ride” or “crawl into my ambulance” or “I found the key to the universe in the engine of an old parked car.” But we get a peek at where this ride’s headed in “Spirit in the Night,” one of two tracks (along with “It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the City”) to tell a somewhat coherent story, of Billy and Janie and their friends driving out to a lake on Route 88 for a night of boozing, swimming, fighting, and lovemaking.

“Spirit” become a concert staple and live fan favorite. I recall hoping they’d play it on the radio late at night after everyone else had gone to bed and I sat up listening in the pale halo of the luminescent FM dial.

![]()

Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.: 5 Caddies

Springsteen’s second album mixes the amphetamine-era-Dylan lyricism of Greetings with the cinematic scenecrafting that would become Bruce’s trademark.

We see Spanish Johnny driving up in his “beat-up old Buick but dressed just like dynamite” and Billy with Diamond Jackie “down by the railroad tracks sittin’ low in the back seat of his Cadillac.” But the real gem, of course, on The Wild, the Innocent, & the E Street Shuffle is the rip-roaring “Rosalita (Come Out Tonight)” which, despite clocking in at over 7 minutes and never being released as a single in the US, caught fire on FM and made Bruce Springsteen a nationally known artist.

Like so many tunes on albums to come, a car ride gets “Rosalita” rolling:

You pick up Little Dynamite, I’m gonna pick up Little Gun

And together we’re gonna go out tonight and make that highway run.

The song became the standard show-closer for Springsteen up until the Born in the U.S.A. tour, no doubt bolstering Bruce’s reputation as the rock and roll laureate of the American automobile, and maybe starting to chap Billy Joel’s ass. Album score: a respectable 3.5 out of 5 Caddies.

![]()

The Wild, the Innocent, & the E Street Shuffle: 3.5 Caddies

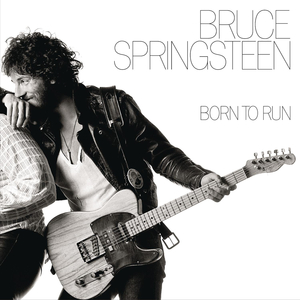

Born to Run

Columbia was ready to cut Springsteen loose if his third album didn’t produce a solid hit. (Nevermind they’d dropped the ball by failing to release “Rosalita” as a single.) Well sir, Born to Run did not disappoint them, racing to #3 on the charts and catapulting Bruce to bona fide rock star status. Both sides of the record open with car ballads, “Thunder Road” and the Top 40 title-track, both telling the story of a young man entreating his lover to escape with him, the first Springsteen songs with car rides at the center of everything.

With just two carless tracks, the four-Cadillac Born to Run revolves around the automobile in a way that not even the five-Caddy Greetings did. Bruce Springsteen’s car was Zane Gray’s horse, Herman Melville’s ship, the simultaneously literal and metaphoric vehicle of freedom and opportunity and all the risks that come with chasing them.

Certainly Springsteen wasn’t the first American writer plying that symbol, but Born to Run may have been its most stirring expression since Kerouac’s On the Road. Because seriously, this stuff is brilliant:

All the redemption I can offer, girl,

Is beneath this dirty hood.

With a chance to make it good somehow,

Hey, what else can we do now

Except roll down the window

And let the wind blow back your hair?

Well the night’s busting open.

These two lanes will take us anywhere.

We got one last chance to make it real,

To trade in these wings on some wheels.

Climb in back, heaven’s waiting on down the tracks.

Oh, come take my hand.

We’re riding out tonight to case the promised land.

Of course, the flip side of that promise is the chance you won’t make it, and admitting that in America there’s no net to catch you if you fail. The album’s title track sees the highway not so much as an opportunity to seize if you dare, but just the only desperate alternative to being ground down by staying where you are, in a “death trap” of a town that “rips the bones from your back.”

Like the lonesome gunslinger and the train-jumping hobo before him, the highway rider runs on equal parts hope and desperation:

The highway’s jammed with broken heroes

On a last chance power drive.

Everybody’s out on the run tonight,

But there’s no place left to hide.

Together, Wendy, we can live with the sadness.

I’ll love you with all the madness in my soul.

Someday girl, I don’t know when,

We’re gonna get to that place

Where we really want to go

And we’ll walk in the sun.

But till then, tramps like us,

Baby, we were born to run.

This tug-of-war between opportunity and failure will power Springsteen’s lyrical engine from this album forward. And for much of that journey, the automobile will dominate his symbolic landscape.

![]()

Born to Run: 4 Caddies

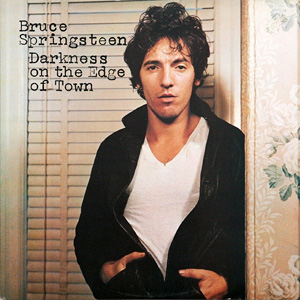

Darkness on the Edge of Town / The Promise

Having earned some screw-you money with Born to Run, and embroiled in the legal wranglings that seem to follow hit records like hangovers do weddings, it took Springsteen 3 years to release his next album, with tracks selected from some 70 or so tunes he’d written, a few of which he farmed out to other artists, most notably “Fire” and “Because the Night.” Also clocking in at 4 out of 5 Caddies, Darkness at the Edge of Town picks up where Born to Run left off, following his characters or their analogs into the next phase of their lives, a typically American working class experience foreshadowed by the white T-shirt, yellowing wallpaper, and plastic slat-blinds in Frank Stefanko’s cover photo of Bruce at his New Jersey home.

Darkness tells the stories of men and women “working all day” and “waiting for a moment that just won’t come,” waking up with a fear in their guts that “it’s all lies” and the only gates waiting for them are the ones outside the factory. The music, though, lends it all a nobility and a grandeur that makes you want to turn the radio up full blast.

At the heart of the album is the 7-minute car ballad “Racing in the Streets.” The young couples who once barreled off down Thunder Road have since cased the promised land and come to discover that the highway inevitably leads to a choice between an eternal shiftless drift or settling down in a town just like the one they escaped. Having chosen the latter, the street’s just a place for an endlessly repeated race to nowhere, night after night, as lonesomeness cools their hearts and age starts to show in their eyes. Turns out, there was no redemption under that dirty hood after all. So for the first time in Springsteen’s lyric world, they turn to God’s creation, and go down to the sea to “wash the sins” from their hands. Or at least that’s what they intend to do.

![]()

Darkness on the Edge of Town: 4 Caddies

In 2010, Springsteen released a collection of more than 20 songs from the Darkness sessions, including “Because the Night,” “Fire,” and his concert classic “The Promise,” the first song he wrote after the success of Born to Run. Promises and their inevitable breaking are replete in Springsteen’s work — the promise of religion and the American dream, the promises we make to our lovers and our children, and so many we make to ourselves.

In the title track to this retrospective, Bruce spells out what Darkness allowed us to figure, and bares the inner conflicts of a fellow who, much like the disillusioned biker at the end of the road-epic Easy Rider, looks at success and thinks, “We blew it.”

When the promise is broken you go on living,

But it steals something from down in your soul.

Like when the truth is spoken and it don’t make no difference,

Something in your heart goes cold.

I followed that dream through the southwestern flats

That dead ends in two-bit bars,

And when the promise was broken I was far away from home

Sleepin’ in the back seat of a borrowed car.

Thunder Road, for the lost lovers and all the fixed games;

Thunder Road, for the tires rushing by in the rain;

Thunder Road, Billy and me we’d always say,

Thunder Road, we were gonna take it all and throw it all away.

It’s interesting that although this collection ranks a respectable 2.5 out of 5 Caddies for new releases, the material that got into Darkness is much more car-heavy, 80% of the tracks rather than 50% in what was left out. Springsteen’s return to car-as-icon isn’t a habit or a crutch, it’s an intentional motif, one he takes his time exploring and reshaping, like Degas’ dancers, Monet’s water gardens, and Kahlo’s self-portraits.

For Springsteen, the commercial success of Born to Run wasn’t something to grab hold of and ride as far as it could take him. It was something he had to throw away if he wanted to explore any other roads.

![]()

The Promise: 2.5 Caddies

The River / The Ties That Bind

It took a double album to encompass everything Springsteen was trying to do musically by the late 1970s: capturing the joy of a great rock and roll show, continuing the stories of the characters who’d come to populate his lyric universe, wrestling with issues of family, work, and an economic recession.

Bruce took some heat from fans of the epic Born to Run and the gritty Darkness on the Edge of Town for putting out a “party record,” and sure, tracks like “Cadillac Ranch” and “Crush on You” are party tunes no doubt. Sides 2 and 3 were our kegger songs, blasting from the windows and ticking off the neighbors as we all sang along off-key. But under The River’s often bubbly surface, deeper currents are flowing.

Sometimes, anyway. I mean, “Ramrod” is just gonna be rock and roll no matter how many times you listen to it.

The River was Springsteen’s first number one album and yielded his first top 10 hit, “Hungry Heart,” which for me is the quintessential Springsteen tune, with its ringing piano, loping beat, swaying melody, tales of love affairs that seem equally fated and doomed, and yes, driving off into an imagined freedom that ends up looking a helluva lot like the place you left.

While caught up in its infectious singalong bonhomie, it’s easy to overlook that it commences with the narrator offhandedly abandoning his wife and children in Baltimore. “Like a river that don’t know where it’s flowing,” he reflects, “I took a wrong turn and I just kept going.” Yet tellingly, this reportedly random drive ends up across the Chesapeake Bay in the same town where he met a previous lover, obviously still on his mind, with whom he “fell in love [then] ripped it apart.”

The final verse of “Hungry Heart” is almost an elixir of Springsteen’s lyrical ethos, the driving force (pun intended) behind all his characters, encapsulating both our inescapable need for love and belonging, and our hollow insistence on chasing an independence we can’t seem to abide once we have it:

Everybody needs a place to rest. Everybody wants to have a home. Don’t make no difference what nobody says, ain’t nobody likes to be alone.

On this album Springsteen anchors the themes that will frame the remainder of his career as a writer, and at their heart is our inability to escape ourselves and the consequences of what we do, our human tendency to bend back toward our past, just as Springsteen the lyricist continuously re-explores his troupe of characters — Billy, Mary, Bobby, Janie, Frankie — in the myriad streets, bars, houses, factories, cars, and open roads they perpetually inhabit.

And it’s here where the road and the river become two sides of the same coin, one of our making and the other of God’s, but both offering a promise of something else, something better. A promise that’s inevitably broken, sure, but we keep believing in it anyway, because the alternative’s too soul-crushing to accept.

All but four songs on this double album mention cars and riding. A few, like “Cadillac Ranch” and “Sherry Darling,” are about cars or riding. It closes with a slow piano tune concerning a “Wreck on the Highway” that the narrator can’t get out of his head. In The River’s final scene, we see a man crawl into bed with his sleeping lover and fold his arms around her, unable to shake an acute awareness of everything’s eternal fragility.

![]()

The River: 4 Caddies

In 2015, Springsteen released a retrospective box set for The River’s 35th anniversary, The Ties That Bind, containing 11 unreleased songs from those sessions. And as with The Promise, the material that didn’t end up on the original album is less car-heavy than what did, in this case 3.5 Caddies compared to The River’s 4. (As a reminder, the Caddy rankings don’t include any previously released titles.)

Lyrically, there’s not much new here. What’s interesting, though, is how often Springsteen chooses to drop those songs that say outright what the included tunes made us feel. Like the narrator of “The Time That Never Was” who is “longing for another world, another life” yet finds his journey “fueled not by the future, but by a past” — not “the” past, mind you, but “a” past, one he invents for himself and chooses to believe in, even though it “never was,” just as unreal as the imaginary life he can’t stop hoping for.

Or the story of “The Man Who Got Away,” in which a guy whose existence is a never-ending commute immerses himself in Hollywood fantasies of bandits who escape at the end of the show, so that “for two hours I can believe the man who got away was me.” If anything, contrasting these outtakes with the released album reveals a lyricist who’s come to master the art of the vignette, a writer working within the claustrophobic format of the pop/rock lyric whose finest compositions, like Picasso’s line drawings, tease all sorts of rich and kinetic scenarios from the mind.

![]()

The Ties That Bind: 3.5 Caddies

Nebraska / Born in the U.S.A.

If you’ve heard Nebraska and Born in the U.S.A., you probably think I’m crazy to lump them together. But as bipolar as these two records are in their moods and styles, the songs are taken from a batch of material composed during a single stretch of time.

Just considering the finished product, it’s as if The Scream and American Gothic had both been painted by the same artist simultaneously. But if you listen closely, it’s easy to imagine, for example, “Open All Night” as an E Street Band rave-up, and “I’m on Fire” as a brooding Nebraska nocturne.

In January of ’82, Springsteen set up a small four-track recording studio in the bedroom of his New Jersey home. In a marathon session that same day, he laid down “demos” for four tunes on Born in the U.S.A. and its accompanying singles, and eleven other songs that resisted translation into E-Street-ese.

Springsteen had faced this situation before. When making his first album, producer Mike Appel had pushed for a folky feel with Bruce on guitar and piano, while Springsteen himself favored bringing the band in. They ended up splitting the difference. But apparently Bruce wasn’t in favor of a rehash. So a selection of the four-track material, mostly from the all-nighter but also from later sessions, was released first as Nebraska, and E Street came in to work up the other songs for release as Born in the U.S.A.

With Nebraska, Bruce slumps down into his iconic automobile and floors it. It’s the first Springsteen album to feature a car on the cover, the only album besides Greetings to mention driving or riding in every song, and the only record in which cars and rides undergird the majority (6 out of 10) of the stories: “Nebraska,” the tale of Charlie Starkweather and Caril Fugate’s murder spree through Nebraska and Wyoming; “Atlantic City,” in which a desperate man plans to meet up with his woman there and light out for the territory after he “does a little favor” for someone; “Highway Patrolman,” the haunting account of a lawman pursuing his own “no good” brother; “State Trooper,” narrated by a man praying for the law not to stop him; “Used Cars,” about the stigma and pride we associate with our material possessions; and “Open All Night,” the musings of a night-shift worker on his way to his lover’s house.

Half of the songs on Nebraska, all the first six except “Mansion on the Hill,” feature criminals and their pursuers, putting the listener in the viewpoint of the fellow in “The Man Who Got Away,” waiting to see if the rebel outlaws can escape the long arm of the law. In the title track and “Johnny 99,” though, we see one man headed defiantly to the electric chair, and another begging the judge to send him there. The others end in the air, with the fugitives as yet uncaught, but for how long?

Three of the remaining tunes explore the author’s crumbling relationship with his father, who first appears driving the narrator as a boy out to admire a mansion neither one of them will ever see the inside of, then showing off a “brand new used car” to the neighbors much to his son’s embarrassment, and finally moving away without even letting his adult son know. All that remains is a house “shining across this dark highway where our sins lie unatoned.”

What stands out most about these tunes is the marked absence of returning. The characters here don’t end up where they started, or in a place just like it, as they have in so many previous songs. Instead, they go nowhere at all, or are caught and locked up, or else vanish into the ether never to be seen again. Even the narrator of “Open All Night,” driving through the dark “to get back to where [his] baby lives,” is abandoned by the songwriter mid-journey as the sun rises behind the refineries.

In the end, Springsteen himself can’t help but return to the theme he’s been shaping and reshaping for the past decade. In the closing track, the narrator passes a man standing along the roadside with “his car door flung open” and poking at dog’s body with a stick, “like if he stood there long enough that dog’d get up and run.” At the end of the day, the narrator observes, despite all evidence to the contrary, “people find some reason to believe.” Whether this constitutes insanity or redemption is left up to the listener.

![]()

Nebraska: 5 Caddies

Sometime in the summer of 1984 I was driving through Atlanta on the half-built downtown connector when a soaring synth chord and hammering drumbeat came busting through the speakers. Then out rolled Bruce’s voice in a bellowing rasp that stood the hairs up on the back of my neck:

Born down in a dead man’s town,

The first kick I took was when I hit the ground.

You end up like a dog that’s been beat too much

Till you spend half your life just covering up.Born in the U.S.A.,

I was born in the U.S.A.

When the full band kicked in I spun that volume knob as far to the right as it would twist. I could barely keep from closing my eyes just to hear it better. When the band came roaring back from the false fade, a fuse blew and the radio cut off. I drove the rest of the way home in silence, then when I got into town I swung by a friend’s house, walked into the kitchen, and said “I just heard the song of the decade.”

Born in the U.S.A. was the leanest on cars of all Springsteen’s albums to date, though it still rates 3 out of 5 Cadillacs. Even the two wide-open car/road songs, “Darlington County” and “Working on the Highway,” end up veering off into dalliances and arrests. The remaining tracks mention cars incidentally or not at all. This record prefers spending its time indoors, where couples dance in the dark, where men lie awake in bed feeling the walls close in and sweating into their sheets, and where for the first time a pair of friends can share a drink in a bar or a living room without fighting the urge to go busting loose into the night.

This is also Springsteen’s first album with every tune sung in first person, from “I” and “we.” There’s no voice-of-God narration, viewing it all from an unaffected distance. And unlike Nebraska — which itself features just one third-person narrative, “Johnny 99” — Born in the U.S.A. is almost entirely bereft of characters with recognizable names. Kate, Bobby Jean, and Wayne² show up only on this album. Aside from Bobby, who gets a fleeting nod as an absent ex-husband, the sole familiar name here is Joe, the hard working, can’t-catch-a-break narrator of “Downbound Train” who blatantly rehashes “My Father’s House” off Nebraska in a scene at his ex-wife’s home.

I don’t think it’s any coincidence that Springsteen’s own life was shifting gears as he released this collection coming entirely from the first-person voice and turning away from his most familiar names and scenes. Facing up to the exhaustion and depression he’d been living with, he started paying attention to his diet and working out, and was committing to a long-term relationship. His characters were both changing up and settling down right along with him.

But true to form, they can never get entirely comfortable. Hardly anybody in the Springsteeniverse ever does. Even when life seems pretty damn good, a fellow can’t help but worry he’ll grow old with nothing but memories of his youthful “glory days” to show for it all. And when Kate and her husband drop their half-formed plans to head south, the man takes their son on the same drive through town that he had as a boy, a ride which presaged race clashes and the textile industry bust.

Born in the U.S.A., with its seven top-10 hits, vaulted Bruce Springsteen into the realm of international superstardom. And as with The River before it, the album drew criticism from some old guard fans for its unabashed pop veneer. But by splitting off the darker material onto Nebraska, Springsteen managed to channel all his newfound energy into this brilliant gem, one that glittered so brightly it was easy to overlook the human flaws at its interior which lend it weight and character.

![]()

Born in the U.S.A.: 3 Caddies

Tunnel of Love

On 1987’s Tunnel of Love, art becomes life becomes art. Like a character in one of his own songs, Springsteen’s personal and professional successes have begun to dissolve into a broken marriage and broken-up band. And once again, on this 2.5 Caddy album, the car and the road are the avatars of that transformation.

On the cover we see an artist who’s made good on the promise from Born in the U.S.A.’s “Dancing in the Dark” to change his clothes, his hair, his face. Gone are the torn denim, unruly locks, and unshaven scruff of previous covers, along with the faded dashboard of Nebraska, the album whose sloping horizon, grainy exposure, and top-and-bottom-framed title cards are reproduced on Tunnel’s layout. Taking their place is a careful curation of elements — the black suit, white button-down, bolo tie, smooth coif, cool lean, and, of course, a café au lait Cadillac Coupe de Ville — all cribbed from the styles and songs of Chuck Berry, an earlier generation rock-and-roller also known for his tunes about cars, dancing, the USA, and a kid named Johnny.

And yet, this is no knock-off. Like a scratch-built roadster, or for that matter Springsteen’s own recursive lyric motifs, the cover image takes pieces of the past and rearranges them into something that seems entirely new and custom, despite being crafted from spare parts.

The album’s title harkens back to the amusement parks that set so many scenes in his first three records. And once again, Springsteen follows a rousing blockbuster with more subdued and challenging material. Recorded mostly at home like Nebraska, and making scant use of the E Streeters, Tunnel of Love somehow manages to be a thoroughly ’80s pop record — synths, drum machines, and all — and one of the most enduringly acclaimed albums of Springsteen’s five-decade career.

Lyrically, the most important track on Tunnel is easily the Nebraska-esque “Cautious Man,” in which Billy is incarnated as a hitch-hiking “man of the road,” always “looking over his shoulder” and eyeing the world with distrust, until finally love finds him and he marries and settles down. But unlike all the previous Springsteen characters who exit the highway only to find themselves trapped by dead-end jobs, inescapable debts, and petrifying routines, Billy builds something new “with his own hands,” a “house down by the riverside” (echoing the famous African American spiritual) for himself and his wife.

Here, in the space between the road and the river, the human promise and the divine promise, the couple live out “happy days and loving nights.” But like the narrator of the album’s top single “Brilliant Disguise,” who admits “I damn sure don’t trust myself,” Billy can’t shake the feeling that “the seed of betrayal” might take root in his “restless heart.” And sure enough, one night he abandons his sleeping wife, dressing in the dark and walking down to the highway in the moonlight.

What happens next is a first in Springsteen’s lyrical world — “when he got there, he didn’t find nothing but road.”

Billy simply can’t see the road as a symbol or a promise anymore. It is just what it is. There’s no freedom in it, or in any place it leads to. Returning home and kneeling in the moonlight at his bedside like some penitent at an altar, he watches his sleeping wife’s face as “the beauty of God’s fallen light” illuminates their bedchamber.

It’s at this point that the songwriter also lets go of his most productive motif, which going forward will never entirely vanish but will only sporadically rise to the overshadowing position it has occupied in Springsteen’s writing so far.

![]()

Tunnel of Love: 2.5 Caddies

Human Touch / Lucky Town

After five years away from studio recording, Springsteen released Human Touch and Lucky Town on the same day in the spring of 1992. Human Touch, recorded without the E Street Band, is Bruce’s first co-written album (with E Street keyboardist Roy Bittan) and its lyrics bear scant resemblance to any of his previous work.

Not only are his usual characters almost entirely absent — John and Bobby have turns as narrators, while Gloria and Doreen each make their sole appearances, and Rambo and Elvis show up on screen — but the album is also practically devoid of Springsteen’s signature cinematic storytelling with its deftly sketched locations and tight dramatic action. In its place we find vaguely defined personas occupying equally nebulous spaces, coupled with abstract proclamations unanchored to time or place, such as this opening stanza from the title track:

You and me, we were the pretenders.

We let it all slip away.

In the end what you don’t surrender,

Well, the world just strips away.

Not that this style is entirely new or anything. “Streets of Fire” off Darkness on the Edge of Town is written like that, for instance, and “Cover Me” on Born in the U.S.A. It just hasn’t been usual to see so much of it in one place. And anyway, how “Streets of Fire” is sung is likely more important than exactly what’s being said. (Surprisingly, “Streets” isn’t a “car song,” by the way.)

Aside from “Soul Driver” in which the driving is entirely metaphoric, the tracks on Human Touch barely mention cars, roads, or riding. And when they do, the references are either incidental (“I hopped into town for a satellite dish / I tied it to the top of my Japanese car”) or clichéd (“life ain’t nothing but a cold hard ride”).

Debuting at #2 on Billboard as thirsty fans rushed to get their fix after half a decade of drought, the album met with mixed and sometimes brutal reviews and has not aged well. It now ranks among the least appreciated albums by Springsteen’s fan base.

While Lucky Town is equally sparse on named characters — Billy makes a brief cameo, as do Bruce Lee, Moses, and Jesus, while “Souls of the Departed” features two surnamed one-timers, little Raphael Rodriguez and “young Lieutenant Jimmy Bly” — it’s much richer in scenecrafting than Human Touch, much closer to classic Springsteen. Like Born in the U.S.A., all the songs on Lucky Town are narrated from first-person perspective, and there’s a house-smell of autobiography to it, especially “Local Hero” which tells the true story of Bruce finding a photo of himself on sale at a store in his hometown, and “Living Proof” describing the birth of Springsteen’s son.

It’s impossible (for me, anyway) not to notice the lyric parallels between the final stanza of “Cautious Man” and the first stanza of “Living Proof.” The scene opens in a “dusky room” occupied by a husband and wife. The illuminating moon has moved metaphorically from outside the window to inside their infant child, who cries as though he has swallowed it, where it emanates not “God’s fallen light” but rather “the Lord’s undying light.”

Even on the cover of Lucky Town, Springsteen seems to be playing against Tunnel of Love, contrasting the times of fulfillment and dissolution (respectively) when each was conceived. While the broad compositional elements are the same — Bruce leaning back with his hands in his pockets, looking out at the viewer, framed by top and bottom title cards — the brilliant disguise is sloughed off. There’s the rumpled clothing, tousled hair, and scruffy jaw of his early covers, along with the bared chest, pendant necklace, and honest smile reminiscent of Born to Run, as the word LUCKY streams down from above onto the artist‘s right shoulder.

Noticeably absent, of course, is the automobile, which is equally absent in this album’s lyrics. Its sole mention comes at the start of “Local Hero” in which Bruce spots his photo in the store window while driving through town. For the moment, at least, Springsteen has gotten almost completely out of the car.

![]()

Human Touch / Lucky Town: 1 Caddy

The Ghost of Tom Joad

Three years after his Lucky/Human double release, Springsteen returned to form with The Ghost of Tom Joad, a spiritual and sonic cousin to Nebraska populated with characters pressed by circumstance into choosing between the frying pan or the fire. The album takes a long, unblinking, unromantic, yet deeply sympathetic look at the lives of drug mules, manual laborers, ex-cons, soldiers, factory workers, drifters, and undocumented immigrants and the patrolmen paid to catch them.

It’s no surprise, then, that the road and the cars that run on it also return to center stage, earning Joad 3.5 out of 5 Caddies. In automobiles, folks smuggle or buy drugs, set out searching for work, flee from crime scenes, pursue lawbreakers, carry kin to their graves, or make their homes.

Typical of the material on this album is the haunting “Straight Time,” a song lifting its title from a 1978 Dustin Hoffman film about a parolee who finds himself just as trapped outside prison as he was inside, and decides there’s no point or use in staying honest. On this track, even the bonds of family are rubbed raw by Charlie’s past, as his wife never completely trusts him, and his uncle who “makes his living running hot cars” helps the couple financially while reminding Charlie to “remember who your friends are.”

Hampered by a muddy production that makes the lyrics difficult to discern despite the sparse musical arrangements, and lacking Nebraska’s occasional respites from desperation, Joad was the first Springsteen album not to go platinum, even while garnering widespread critical acclaim. And while I like Eric Dinyer’s art as much as the next guy, the inscrutable cover subject likely didn’t do the record any favors either.

![]()

The Ghost of Tom Joad: 3.5 Caddies

The Rising

Bruce Springsteen follows his muse, writing when inspiration strikes, often in intense spates of astonishing creativity. The 9/11 attacks in 2001 jolted him out of a six-year lull, sparking a burst of songcrafting that produced his first #1 album since 1987’s Tunnel of Love, the double-platinum, Grammy-winning, critically acclaimed The Rising.

Reunited with the E Street Band after nearly two decades, Bruce pulls out of the skid and finds his groove by blending his pre- and post-1990 styles to sketch evocative scenes that are a lot less nailed down than his classic material, much more open to interpretation, salted with a bit of surrealism, and replete with religious and spiritual imagery, like this stanza from the title track:

Left the house this morning,

Bells ringing filled the air.

Wearin’ the cross of my calling,

On wheels of fire I come rollin’ down here.

Here we’re handed the payoff from Human Touch’s lyrical adventures, a writing style the artist will stick with for the long haul. So far, anyway.

With the exception of Mary, Bruce’s faithful cast of characters have at last retired. And the automobile, while not yet rolled off to the barn, slips to the background, to be cranked up only when needed. A “long black line of cars snakin’ slow through town” joins a disjointed list of ominous images in the foreboding surrealistic landscape of “The Fuse.” A guy without his gal feels like “an ice cream truck on a deserted street” in the metaphoric plaint “Waitin’ on a Sunny Day.”

Oddly enough, the track “Further on (Up the Road)” can’t be counted as a car song because there are no cars in it, and whether the characters are riding or walking remains ambiguous. Which leaves the album at just one and a half out of five Cadillacs.

![]()

The Rising: 1.5 Caddies

Devils & Dust

In 2005, Springsteen took a left turn at Albuquerque into the country-fried acoustic solo album Devils & Dust. Unlike Tom Joad, the production’s clear as a bell, and the songs are a little easier on the soul than Joad or Nebraska.

Devils & Dust debuted at #1 but tapered off after Columbia’s distribution deal with Starbucks fell apart over some, let’s say, candid lyrics sung from the point of view of a john with his date. Well that, and Bruce bad-mouthing corporations on stage and not wanting Starbucks labels on his stuff.

D&D collects back-catalog material going back about a decade that hadn’t made it onto any earlier releases, so except for the country-twang-meets-Dylan-twang feel of the performances there’s not a lot holding it together. There’s plenty of movement — a bus, a train, rivers, horses, walking — but only a couple of car songs.

As different as this record sounds from The Rising musically, the writing is even truer to that form. Take these verses from “All I’m Thinkin’ About”:

Blind man wavin’ by the side of the road

I’m in a flatbed Ford carrying a heavy load

With a sweet thing sippin’ on a blueberry wine

On a flat black highway down in Carolina

Black bird slippin’ in a sky of blue

All I’m thinkin’ about is you ….Little boy carryin’ a fishin’ pole

Little girl pickin’ berries straight off of the vine

Brown bag filled with a little green toad

We hook ’em through the lip and throw ’em off of the line

Your sweet brown legs got me feeling so blue

All I’m thinkin’ about is you

Black car shinin’ on a Sunday morn

Mama go to church now, Mama go to church now

Friday night daddy’s shirt is torn

Daddy’s goin’ downtown, daddy’s goin’ downtown

Ain’t no one understand this sweet thing we do

All I’m thinkin’ about is you

It’s like a mosaic. The lines are simple and sparse and visually precise, but the verses are fractured and open. We’re riding down the road, then we’re home, maybe or maybe not with the same people. The couplet about the girl picking berries splits the two lines about fishing. And is “you” the woman in the cab drinking wine? Or not? Is Daddy coming home or going downtown to “you”? The pictures are easy enough to see, but what’s happening in them depends on your angle.

The cast here’s crowded with one-timers — Rainey Williams and his mother Lynette, the boxers Jack Thompson and John McDowell, a lover called Leah, nameless moms and dads, and Fiona Chappel and sons Tyler and Oliver by way of dedication — along with God, Jesus, and of course Mary whose namesake Maria shows up in a pair of bedroom songs, “Reno” and “Maria’s Bed.” Our old stalwart Bobby puts in a cameo as a comrade-in-arms, and after all these years we meet up with Rosie again, by a campfire under the stars, two kids in sleeping bags within watch and her husband’s hand laid across her pregnant belly. Like the man who writes her, she’s out of the car. But not too far.

![]()

Devils & Dust: 1 Caddy

Magic

In ’07, Bruce and E Street got together for Magic, an album in that classic bar band style they do oh so well. It sold, going platinum despite not a lot of airplay. “Radio Nowhere” and “Girls in Their Summer Clothes” won Best Rock Song Grammys in sequential years, and the critics gave the record high stars.

Rating just one and a half Caddies, Magic is a fine example of how Springsteen at this point is deploying the motor vehicle sparingly in his lyric landscape, just where and to the degree it’s useful.

In “Livin’ in the Future” it’s an accent, “rollin’ through town, a lost cowboy at sundown,” just a brushstroke to set the scene. In “Gypsy Biker” it is motif and MacGuffin, as friends of a fallen soldier memorialize him by torching his motorcycle in a canyon.

For “Last to Die” it’s a narrative device, holding the stanzas together as a family roll down the highway while news of the war comes through the radio. And for “Radio Nowhere” it’s the setting, at once frenzied and claustrophobic, inside which the narrator remains utterly isolated while plugged into the world through a one-way connection.

![]()

Magic: 1.5 Caddies

Working on a Dream

With the eclectic studio-pop collection Working on a Dream, Springsteen became a gold- rather than platinum-selling artist. And although his albums still reach the top couple of pegs on the charts, as of this writing none of Bruce’s subsequent records have gone gold in the US.

To be honest, there’s not much to say about this album here because motor vehicles simply aren’t on it. We catch just two glimpses — a “here’s one for the road” toast in “Life Itself,” which implies a ride so I’m counting it, and a woman getting into a car in the opening stanza of “This Life.”

That’s it. As of the dawn of 2022, this is about as “out of the car” as Bruce is ever going to get.

![]()

Working on a Dream: 1 Caddy

Wrecking Ball

With 2012’s Wrecking Ball, Springsteen and a partially E Street amalgam return to Bruce’s classic big sound and gritty characters, while hanging on to some of the last album’s stylistic ranginess — take a boomy Irish reel, for instance, about a guy pocketing a .38 and heading downtown “lookin’ for easy money” — all served up with a side of irony and a generous dollop of Jesus-railing-at-the-Temple.

The automobile is as scarce on this outing as it was on the last one. We see a “jack of all trades” rebuilding engines, and get probably the most tangentially metaphoric reference to pass muster: “all our little victories and glories have turned into parking lots.”

On this record, though, the absence of the road and its travelers is more conspicuous, because if anything this is an album about standing one’s ground. “My home’s here,” declares the title song, “c’mon and take your best shot, let me see what you got.” Even when folks get the urge to move, they aren’t off to drift the open road. More likely, they’ll catch a train to a destination, a place they can settle down where tractors bounce through sun-slanted fields in a “land of hopes and dreams.”

The guy digging dirt or hammering shingles isn’t looking to escape, he just wants a fair shake right where he is. And the guy who hops the train isn’t searching for freedom, he’s looking for a steady job and warm beds for the kids. It’s an older perspective, a father’s perspective, one that’s learned the value of home the hard way, despite its hassles and repetitions, its disappointments and flat out hard-ass labor.

![]()

Wrecking Ball: 1 Caddy

High Hopes / American Beauty

A stylistic admixture reminiscent of Working on a Dream, 2014’s dual release of High Hopes and American Beauty was a reach-back, drawing on a decade of unreleased songs in much the way Devils & Dust had done while tossing in a few reworks and cover tunes. Like Nebraska and U.S.A. three decades earlier, Springsteen split the material across a band album (Hopes) and a home-studio EP (Beauty).

Together, they also comprise the first Springsteen release in nearly two decades with automobiles appearing in at least half the new tracks. I reckon the man can only stay out of the car for so long.

But in High Hopes, the automobile-as-icon has almost entirely vanished.

The precision with which Springsteen employs car imagery in his 21st century writing is beautifully exemplified in “The Wall,” a tune about a man visiting the Vietnam memorial in Washington, DC. “I’m sorry I missed you last year,” says the narrator, “I couldn’t find no one to drive me.”

This negative space, this absence of the car, speaks volumes. Whether we’re consciously aware of it or not (probably not), that single detail defines this character’s station in life. Can he not afford a car? Has his license been revoked? Whatever the situation, his carlessness places him squarely outside the American dream.

Meanwhile, as he lays a pack of smokes and a bottle of brew beneath Billy’s name — Billy, Bobby, and Frankie all return from hiatus on this record — “limousines rush down Pennsylvania Avenue rustling the leaves as they fall.” Those in positions to send men to war ride like emperors in cars they don’t even have to drive. Here, the automobile is a symbol of division, between the haves and have-nots, yes, but also between those who command and those with no choice in the matter.

And this dichotomy scales down, working even among the have-nots, or at least the have-lesses, as we see in “Harry’s Place,” about a local crime boss:

When Harry speaks, it’s Harry’s streets.

In Harry’s house, it’s Harry’s rules.

You don’t want to be around, brother, when Harry schools.

Its Harry’s car, Harry’s wife, Harry’s dogs run Harry’s town.

Your blood and money spit shines Harry’s crown.

Elsewhere, the car is more like stage dressing, presented with a lyric economy born of four decades of practice:

Radio’s cracklin’ with the headlines

Wind in the phone lines

The sun upon your shoulder

Empty city skyline

Four simple lines of between five and nine syllables, yet so evocative. That right there, my friends, is mastery.

Well well well, what have we here? If it’s not a café au lait convertible.

The American Beauty EP, released on the heels of High Hopes, contains four songs from the same pool of material that didn’t fit on the first record but which Bruce felt were also worth releasing. And true to its cover, half the tracks mention cars.

The title song reworks the music from “Frankie Fell in Love” as well as the car lyric from “Down in the Hole” cited above:

Radio’s cracklin’ with the headlines

Somethin’ on your shoulder,

winds in the phone lines.

American beauty, will you be mine

On this highway counting white lines?

But in “Hurry Up Sundown” Springsteen takes us back to his earlier spin on the American auto as an icon of freedom, although these characters don’t seem to need liberation from much except the boredom of the working day. “Change your clothes,” says the singer, “we’ll go for a ride to the other side…. Over here it’s easier to breathe. There’s a place for you and me and there’s no devil here to pay.”

Exactly where or what this “other side” might be isn’t explained. Perhaps it’s nothing more than the freedom to take a ride for no particular reason in the first place.

![]()

High Hopes / American Beauty: 2.5 Caddies

Western Stars

Bronco on the cover notwithstanding, 2019’s Western Stars chalks up an impressive 3.5 Caddies, a density of car tunes not seen on a Springsteen album since 1995’s Ghost of Tom Joad. Sure, there’s horses, but they’re being chased by guys in pickup trucks.

The album kicks off with “Hitch Hiking” a song about precisely that, and it’s unlike any other hitching song in the Springsteen universe, unabashedly idealized and optimistic. This hitcher is no cautious man. He catches rides easily — with a family, a trucker, a kid in a hot rod — and seems to have not a care in the world:

I’m hitch hiking all day long

Got what I can carry and my song

I’m a rolling stone just rolling on

Next up is “The Wayfarer,” a wistful treatment of the midnight rambler, the soul who can’t seem to settle down:

You start out slow in a sweet little bungalow

Something two can call home

Then rain comes fallin’

The blues come calling, and you’re left with a heart of stone

Some folks are inspired sitting by the fire

Slippers tucked under the bed

But when I go to sleep I can’t count sheep

For the white lines in my head

I’m a wayfarer, baby

I roam from town to town

When everyone’s asleep and the midnight bells sound

My wheels are hissin’ up the highway

Spinning ’round and ’round

Where are you now? Where are you now?

Yeah, sure, there’s some nostalgia here, but against the background of an acoustic guitar strum and strings, there’s no grit in it, no sense that this guy is doing anything other than what suits him. And I’m starting to wonder, wait, is this Springsteen?

The title track is a nice bit of wordplay, sung from the point of view of an old actor from the heyday of the Westerns, spinning stories about starring with John Wayne while fans buy him drinks and getting recognized by the young ladies from his appearance in a credit card ad. And yet, he’s not stuck in his glory days. On weekends he tosses a saddle in the bed of his El Camino and heads “east to the desert where the charros, they still ride and rope…. Tonight the western stars are shining bright again.” He’s trading on his past, all right, but he’s living for every day he wakes up to find himself in his own bed, not “down the Five at Forest Lawn.”

Springsteen said of Human Touch and Lucky Town that he tried putting out a happy album but the fans didn’t want it. By now, quite frankly, Bruce doesn’t seem to care what anybody else wants. And it’s liberating.

To be honest, after journeying with Springsteen through his oeuvre — the early Dylanesque romps, the angst and bravado of his classic period, the personal trials and biting social commentary of his mid-life work — Western Stars feels like a cool drink of water at the end of a long dusty ride. Joe comes home from the war, gets married, opens up a little cafe, and lo and behold they run a new highway right by it and he’s set for life. And an old stuntman, banged up and held together with steel pins and rods, wouldn’t trade any of it if he could: “Don’t worry about tomorrow, don’t mind the scars. Just drive fast, fall hard.”

As the album progresses we take a sideroad into regret — past the songwriter who left his love for a shot at making it big in Nashville only to find himself “out on [the] highway with a bone-cold chill” and nothing but “[a] melody and time to kill,” and the nameless man who sets off down the road when he finds he can’t quite make himself believe the assurances that “those are only the lies you’ve told me.”

But we’re not left there. Because “you know, I always liked that empty road. No place to be and miles to go.” Maybe, just maybe, there can be freedom in the road after all. Not in any destination, mind you, not in searching for what you don’t have, but in the road itself, in accepting that we are always betwixt and between, and opening oneself up to the journey.

We’re left at the Midnight Motel, a Western analog to that Kingstown bar, where our humble narrator goes to revisit his past, only to find the place boarded up and empty. So he pours three shots in the parking lot — one for himself, one for his absent lover, and one a libation to their old haunt. When all is said and done, “it’s better to have loved, yeah, it’s better to have loved.”

![]()

Western Stars: 3.5 Caddies

Letter to You

Just when you think maybe Bruce has gotten comfortable in that old driver’s seat, 2020’s Letter to You shifts into reverse, squeaking in at just 1 Cadillac on the 5-Caddy scale. But good lord, what a record! I have to confess, the opening and closing tracks brought tears to my eyes.

I wish I had more to say about Letter here, but my subject constrains me and this article’s long enough as it is. Even the couple of car references we get on this album are brief and oblique. In “Janey Needs a Shooter,” an unreleased tune from the 1970s covered by the late great Warren Zevon with a different set of lyrics, we hear a cop car’s siren wailing outside Janey’s house. And in “Song for Orphans,” another ’70s back-reacher, we get a fleeting metaphoric reference to the Oakies whose jalopies drifted across the American landscape during the Great Depression.

So I tell you what, I’ll let you discover this true gem of an album on your own. What I will say is that by going his own damn way Bruce has landed firmly on his bootsoles, confident of his mastery of the craft and with nothing to prove to anybody but himself and his band, deftly evoking scenes and emotions through word and sound. And I’ll leave you with these lines from the title track:

Things I found out through hard times and good

I wrote ’em all out in ink and blood

Dug deep in my soul and signed my name true

And sent it in my letter to you

I took all my fears and doubts…

All the hard things I found out…

All that I’ve found true…

I took all the sunshine and rain

All my happiness and all my pain

The dark evening stars

And the morning sky of blue

And I sent it in my letter to you.

You sure did, Bruce. You sure as hell did.

![]()

Letter to You: 1 Caddy

Body of work (thus far)

Of course there are some songs we’ve missed along the way. Bonus tracks from retrospectives, concert tracks, and the like. There’s a list below if you want to take a peek at what’s been omitted.

Taking Springsteen’s entire body of work into account, 49% of his songs mention cars, highways, engines, auto shops, and all the other components and haunts of the automobile and those who drive them or come along for the ride. That’s a respectable two-and-a-half out of five Caddies for Bruce’s work thus far, reaching as high as 100% on a couple of albums but never falling below the 15% mark, never dipping down to the half-Caddy or no-Caddy range.

So I’m sorry, Billy, but I guess Bruce never did get out of the car, not completely anyway. And just when you think he’s ready to leave it behind, he cranks it up and takes it out for another spin. Now I take your point, Mr. Joel, but when you read a man’s entire lyric output, it gives you a new perspective. For me, trying to imagine Springsteen without his automobiles, well, it’s kind of like trying to imagine Lichtenstein without his comics, Warhol without his pop culture, Faulkner without his Southern clans, Escher without his interplay of foreground and background.

And frankly, looking back over their entire careers, it’s hard to say what Joel’s was about. Which is no knock on him, every artist is different. But you know what Springsteen is about. Or at least, you do if you’re willing to listen.

Thanks, Bruce. Looks like this is where I get out. I appreciate the lift. And the conversation. It’s been an interesting 48 year ride, Boss. And hey, next time you’re out, I wouldn’t at all mind riding along again.

![]()

Body of Work: 2.5 Caddies

Track Lists

Qualifying “singing about cars” songs by album (newly released material only) in order of release:

Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.

Blinded by the Light Growin’ Up Mary Queen of Arkansas Does This Bus Stop at 82nd Street Lost in the Flood The Angel For You Spirit in the Night It’s Hard to be a Saint in the City

The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle

4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy) Wild Billy’s Circus Story Incident on 57th Street Rosalita (Come Out Tonight) New York City Serenade

Born to Run

Thunder Road Night Backstreets Born to Run Meeting Across the River Jungleland

Darkness on the Edge of Town

Badlands Adam Raised a Cain Something in the Night Candy’s Room Racing in the Street The Promised Land Prove It All Night Darkness on the Edge of Town

The River

The Ties That Bind Sherry Darling Jackson Cage Independence Day Hungry Heart Out in the Street Crush on You You Can Look (But You Better Not Touch) The River Cadillac Ranch I’m a Rocker Stolen Car Ramrod The Price You Pay Drive All Night Wreck on the Highway

Nebraska

Nebraska Atlantic City Mansion on the Hill Johnny 99 Highway Patrolman State Trooper Used Cars Open All Night My Father’s House Reason to Believe

Born in the U.S.A.

Born in the U.S.A. Darlington County Working on the Highway Downbound Train Bobby Jean I’m Goin’ Down My Hometown

Tunnel of Love

Ain’t Got You Tougher Than the Rest Cautious Man Walk Like a Man One Step Up Valentine’s Day

Human Touch

Soul Driver 57 Channels (And Nothin’ On) Real World

Lucky Town

Local Hero

Greatest Hits (1995)

Secret Garden Blood Brothers This Hard Land

Ghost of Tom Joad

The Ghost of Tom Joad Straight Time Highway 29 Sinaloa Cowboys The Line Balboa Park Dry Lightning The New Timer

Tracks

Bishop Danced Seaside Bar Song Zero and Blind Terry Linda Let Me Be the One Iceman Don’t Look Back Roulette Where the Bands Are Living on the Edge of the World Take ’Em As They Come Ricky Wants a Man of Her Own I Wanna Be with You Johnny Bye-Bye Shut Out the Light Frankie TV Movie Stand On It Car Wash Rockaway the Days Brothers Under the Bridge ’83 Man at the Top Pink Cadillac Two for the Road The Wish Lucky Man Loose Change Goin’ Cali

18 Tracks

The Promise

The Rising

Waitin’ on a Sunny Day Worlds Apart The Fuse The Rising

The Essential Bruce Springsteen

American Skin (41 Shots) From Small Things (Big Things One Day Come) The Big Payback Held Up Without a Gun None But the Brave County Fair

Devils & Dust

Maria’s Bed All I’m Thinkin’ About

Magic

Radio Nowhere Livin’ in the Future Gypsy Biker Last to Die

Working on a Dream

This Life Life Itself

The Promise: The Darkness on the Edge of Town Story

Outside Looking In Candy’s Boy Save My Love Ain’t Good Enough for You Fire Spanish Eyes Come On (Let’s Go Tonight) Breakaway City of Night

Wrecking Ball

Jack of All Trades Wrecking Ball

High Hopes

Harry’s Place Just Like Fire Would Down in the Hole The Wall

American Beauty

American Beauty Hurry Up Sundown

The Ties That Bind

Cindy The Man Who Got Away The Time That Never Was Whitetown Chain Lightning Party Lights Stray Bullet Mr. Outside

Chapter and Verse

He’s Guilty (The Judge Song)

Western Stars

Hitch Hikin' The Wayfarer Western Stars Sleepy Joe’s Café Drive Fast (The Stuntman) Chasin’ Wild Horses Somewhere North of Nashville Hello Sunshine Moonlight Motel

Letter to You

Janey Needs a Shooter Song for Orphans

¹ Use of the cover art in this article complies with fair use under United States copyright law: Images are used for identification in the context of critical commentary of the work for which they serve as cover art. They make a significant contribution to the user’s understanding of the article, which could not practically be conveyed by words alone. Each image is placed separately at the top of the section discussing the work, to show the primary visual image associated with the work, and to help the user quickly identify the work. Use for this purpose does not compete with the purposes of the original artwork, namely the artist’s providing graphic design services to music concerns and in turn marketing music to the public. As musical cover art, the image is not replaceable by free content; any other image that shows the packaging of the music would also be copyrighted, and any version that is not true to the original would be inadequate for identification or commentary. Because the image is cover art, a form of product packaging, the entire image is needed to identify the product, properly convey the meaning and branding intended, and avoid tarnishing or misrepresenting the image. The copy is of sufficient resolution for commentary and identification but lower resolution than the original cover. Copies made from it will be of inferior quality, unsuitable as artwork on pirate versions or other uses that would compete with the commercial purpose of the original artwork.(Wikipedia)

² The unreleased song “Delivery Man” from the Born in the U.S.A. sessions features a narrator named Wayne.

Header image: Bruce Springsteen at Veterans Memorial Arena, Jacksonville, FL, 15 August 2008, adapted; original photo by Craig ONeal

Paul Thomas Zenki is an essayist, ghostwriter, copywriter, marketer, songwriter, and consultant living in Athens, GA.